Treating Influenza

In 1912, the United States government established the Public Health Service. The agency, which originated from a system of marine hospitals established in the late 1700s, was responsible for helping the nation battle communicable diseases like influenza. It was ill prepared for the scale of the 1918 pandemic that swept across the country. Among the service’s greatest tasks at the beginning of the pandemic was sharing information about influenza. According to historian Alfred Crosby, “neither physicians nor laymen knew more than a few scary rumors about Spanish influenza, providing the perfect climate for confusion, panic, and proliferation of quack remedies” (49).

In late September the Eau Claire Board of Health advised local physicians to begin recording cases and treat influenza as a quarantinable disease. The Board also shared an excerpt from a Public Health report detailing the signs and symptoms of Influenza. It stated, “…a sharp rise of temperature to 103 or 104, complaint of a headache, pain the back of the photophobia… the throat feels sore; there is congestion of the pharynix (sic)…” The fever, according to the report, lasts three to four days after which time most patients recover quickly. The report concludes that the highly communicable disease is spread by “…the excretions from the nose, throat and lungs” and through materials that spread those secretions.

In October, following advice from the United States Surgeon General, local schools, theaters, and other places of gathering were closed by order of the Board of Health. Although locally cases were few, the Board of Health also worked diligently in October to secure the Montgomery Hospital to serve as a quarantine/isolation hospital. The use of masks at places of employment also rose sharply during this time, and the board organized the administration of inoculations for the public.

The records of the Eau Claire Board of Health, showcased and accessible on this page, detail the efforts and actions of the local Board to guide the medical community during the pandemic.

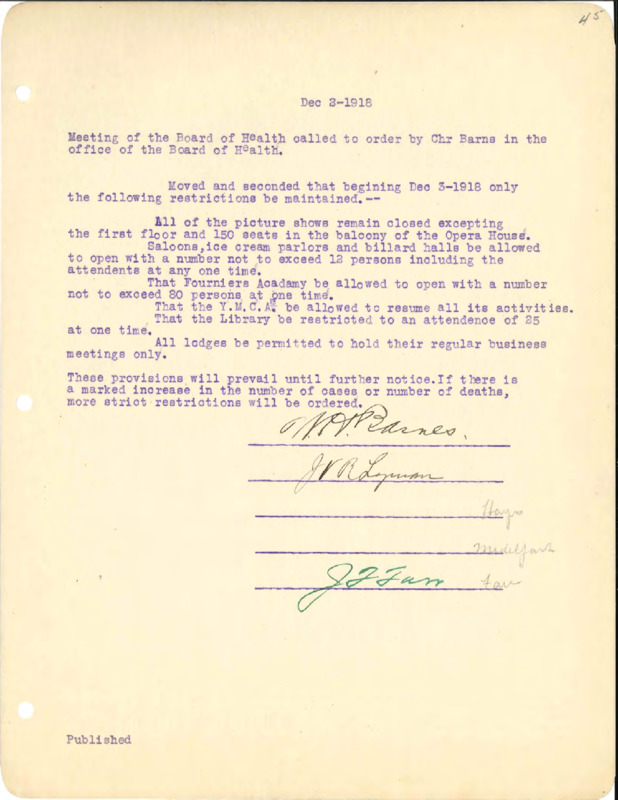

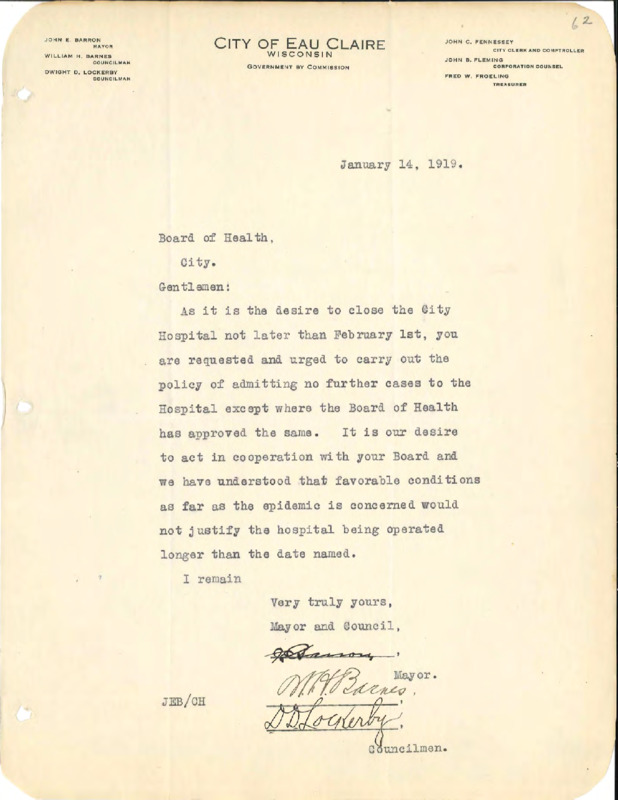

Efforts by the Board of Health to limit the spread of influenza were largely successful in October and November 1918. At a mass meeting on November 23, 1918, consisting of the City Council along with the Board of Health and other interested parties, it was agreed to reopen schools and churches with some precautions. Efforts to further open the community occurred following the board’s December 2nd meeting. December, however, was the most challenging month with the number of cases in Eau Claire soaring during this time. Efforts to reduce restrictions in November and early December may have even contributed to the rise in cases.

The records of an Eau Claire physician, Dr. Roy Mitchell, provide us with an opportunity to understand how cases were treated and the number of patients presenting with influenza in the fall of 1918. Mitchell’s patient register, selections of which are available in this collection (with identifying names redacted) detail the medicine prescribed to patients. The volume of patients recorded by Dr. Mitchell in December of 1918 is most likely a direct result of the rise in influenza cases across the Chippewa Valley that month.

While cases rose sharply in December, the number of deaths remained very low, especially when compared to other communities. The low rate of death may be attributed to the attentive actions of the Board of Health to prepare and educate the community in the months leading up to that spike in December. In a report to the State Health Officer compiled in early 1919, and present among the board’s records, the Board of Health states, “We know of no city large or small afflicted with this diseas (sic) during the epidemic with as small a death rate and we attribute it largely to the precautions taken and the almost universal full co-operation of the public...”