Education

As cases of influenza rose in Wisconsin, local and state Boards of Health stepped in to take action. On October 10th, 1918, the Eau Claire Leader reported the Eau Claire Board of Health had met the previous evening and had agreed to issue a ban on public gatherings, a move which had only been implemented in four other Wisconsin cities at the time. As this announcement was being read by citizens on the 10th, C. A. Harper, secretary of the state board of health issued a notice that a statewide ban would be implemented. Surgeon Major V. G. Heiser later praised Harper for taking an early stand.

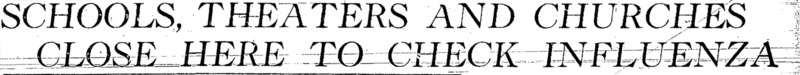

Churches, libraries, theaters and places of amusement, lodges, dancing academy, Y. M. C. A. meetings, pool and billiard rooms, and gatherings of five or more people were banned. Schools were included in this order, and on October 11th, students and teachers were homebound indefinitely.

While initially billed as a “real vacation for school folk” in the newspaper, as no homework had been assigned, it was anything but. One of the first concerns was that students would take advantage of this time off from school to work. An article was published in the Eau Claire Leader on October 15th warning permit officers not to issue work permits to children who may apply. The necessity of sending children to work became a reality for those who were either permanently or temporarily out of work, not excluding schoolteachers.

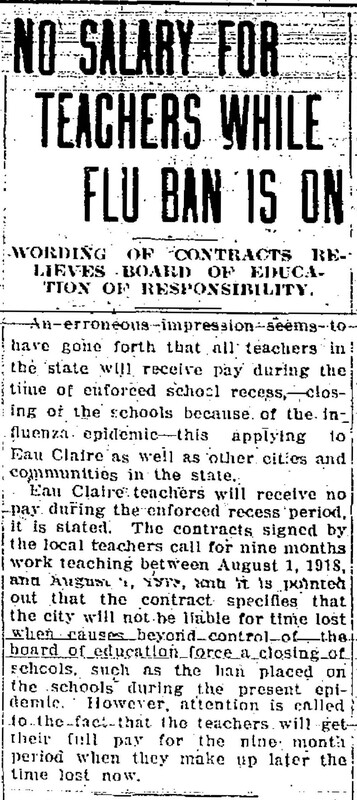

As schools continued to shutter their doors for longer than anticipated, the status of teachers’ paychecks remained unknown. Due to wording in their contracts which specified, “the city will not be liable for time lost when causes beyond control of the board of education force a closing of schools,” teachers were initially told they would not get paid until school was back in session. The state department of education suggested that teachers and school officials should be paid during the closure, but the decision was ultimately left to individual school boards and their contracts.

The discrepancies between state and local decisions also affected the lifting of bans and closures, leaving the end date of the restrictions unknown. When the ban on public gatherings was first reported, the duration was uncertain, but it was reported that “2 weeks is minimum.” The state board of health lifted the statewide ban on gatherings on November 1st, and instead left the decision up to local boards of health. Eau Claire county left the bans in place, which left many citizens frustrated, as can be seen in a Voice of the People article in the Eau Claire Leader on November 10th. The author of the article expresses their dissatisfaction with the continued ban, stating that the county board had not been appropriately handling the situation and many citizens believed schools, churches, and other places of amusement should be reopened.

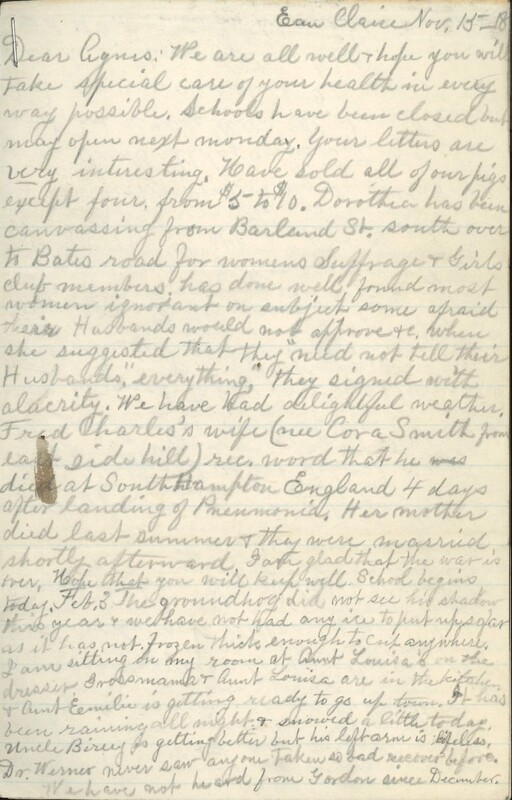

In a letter to her daughter on November 15th, Dora Barland wrote that schools were expected to open the following Monday, November 18th. However, the Eau Claire Leader announced on November 17th that not only would the ban keeping students home be extended, but it would also stretch to include, “clubs, ice cream parlors, and soda fountains,” and masks were now required in stores and offices. Only a week later, however, schools, churches, and saloons were reopened, though with restrictions applied. Schools were allowed to open but were to be, “carefully supervised by nurses, who will send home any pupil appearing ill.

On December 3rd, the Eau Claire State Normal School reopened it’s doors, making sure that a graduate nurse was present each day. One week later, however, it published its decision to close the model school that was part of the college, as well as banning dances and social functions.

As schools reopened, cases of influenza began to rise again. In a move to keep schools open but lessen cases of the flu, the county school board moved “that all children attending school from homes in which there is influenza be excluded from school and that the board of health be requested to furnish the secretary of the board with the names of all families having influenza.” In the same meeting, it was decided to periodically fumigate schools and also to shorten Christmas vacation in order to make up the days lost.

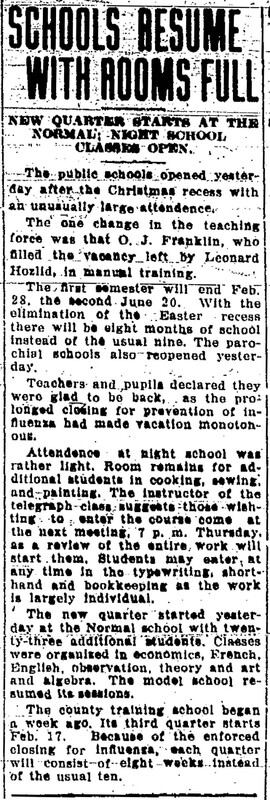

After Christmas vacation, public schools reopened with adjusted calendars which would make up the days they had been closed. Some schools eliminated Easter vacation and extended the school day by 70 minutes. When the new semester began, it was welcomed with open arms by students and teachers alike, declaring that the time off had become “monotonous.”