A Post WWII Nation:

Access, Advancements, & Inequality

The end of the Second World War created a new age of optimism for public health in the United States. With the spread of new miracle drugs like antibiotics and medical advancements such as blood banks, each generation could reasonably expect to live longer than their parents. Diseases that had once decimated populations could now be controlled or even eradicated all together. Perhaps no cure was more celebrated than that of the polio vaccine.

Wisconsin, like the rest of the nation, faced a growing polio epidemic in the early 1950s. The disease affected nearly 40,000 people every year, with 15,000 individuals becoming paralyzed. But the vaccine, first developed by Jonas Sauk, now provided protection against the once dreaded virus.

Seemingly overnight, Health Departments across Wisconsin rallied to immunize thousands of residents. Cases fell rapidly throughout the decade, with less than 100 cases nationwide reported in the 1960s.

Migrant Latinx Workers in Rural Wisconsin

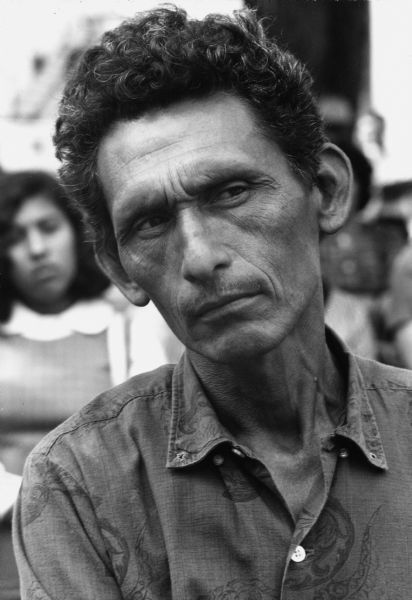

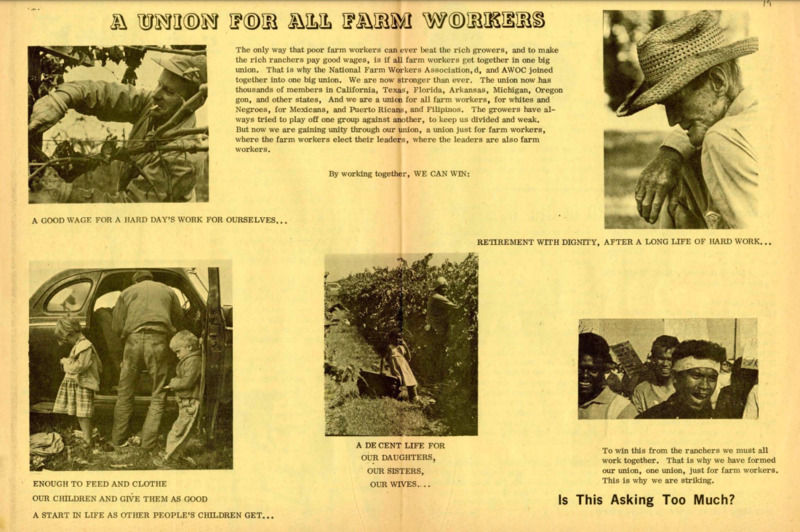

Of course, not all shared equally in these benefits. Poverty and racism continued to separate the have’s from the have nots. This was especially the case when it came to migrant laborers in rural communities. Though migrant labor has long been an essential part of agriculture, the advent of the Second World War accelerated its growth. With the Bracero and H-2 guest-worker programs, men and women from Mexico, Jamaica, and other Caribbean nations came to work on farms across the United States, including Wisconsin.

In 1942, the Bracero Program began as a way to provide cheap rural labor to the US. Policymakers conceived the program as seasonal or short-term, intending for workers to return to home countries after the contracts were completed. The vast majority of the rural workers came from Mexico seeking the promise of job opportunities, social and health benefits, and an improved quality of life. But status and treatment left much to be desired. In fact, L.G. Williams of the Department of Labor referred to the program as “legalized slavery.” Low wages, dangerous work, and hostile employers created major health concerns for workers, and many raised their voices to achieve better conditions.

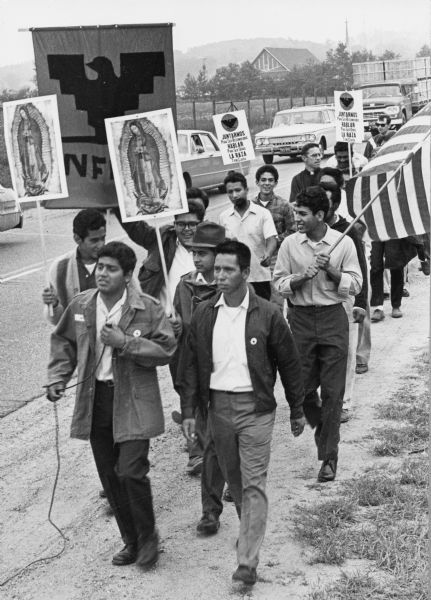

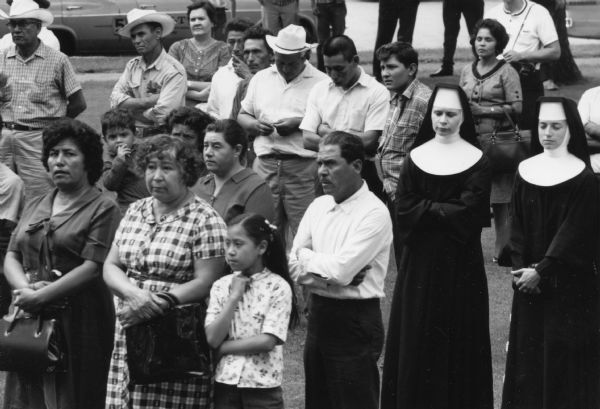

As a consequence of this situation, migrant workers in Wisconsin organized Obreros Unidos (United Workers) under the leadership of Jesus Salas (1944- present). By holding marches, demonstrations, and rallies, they worked to achieve basic social rights, including healthcare and safe working conditions promised through the worker program. For Bracero workers, their Catholic religious beliefs were entwined with their fight for equal rights and healthcare, as they marched under the banner of the Virgen de Guadalupe (Our Lady of Guadalupe).

As the patron saint of Mexico and a figure understood as Mexicans’ most important protector, Our Lady of Guadalupe had long played an important role in Mexican politics, nationalism, identity, and social causes. In rural Wisconsin towns, community members were aware of migrants' beliefs and both the Catholic and Christian churches of the area supported workers' claims and fights.

The Federal Government took note as well. In September 1962, the Kennedy administration passed the Migrant Health Act, providing federal grants for migrant health clinics. That was a step forward in providing health care to marginalized workers. Nevertheless, it did not solve the entire situation and migrant workers kept on looking for other possibilities.

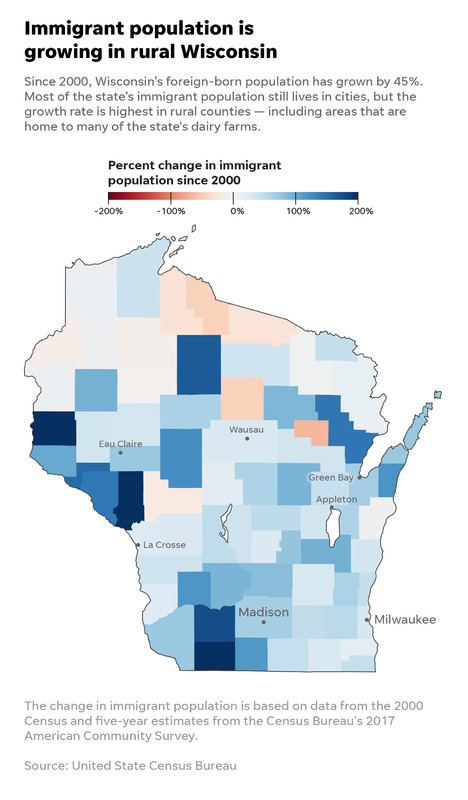

By 1964, the Bracero Program ended, but the reliance of US agriculture on migrant Latinx workers never stopped. In fact, today Latinx immigrants represent 40 percent of the workforce on Wisconsin dairy farms. With a consistent trend of younger populations leaving rural areas in the Midwest, Wisconsin's signature agricultural industry—dairy—would collapse without the labor of immigrant workers, many of them undocumented.