The Progressive Era:

Faith in science & "care for the feeble-minded"

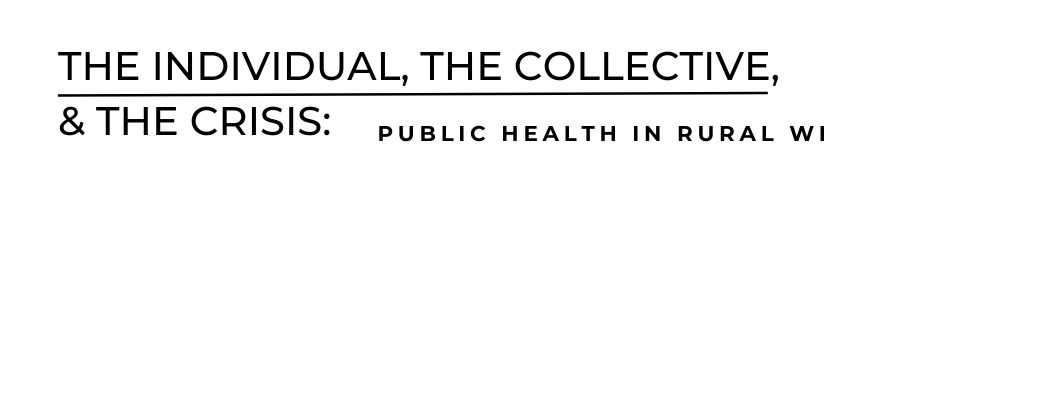

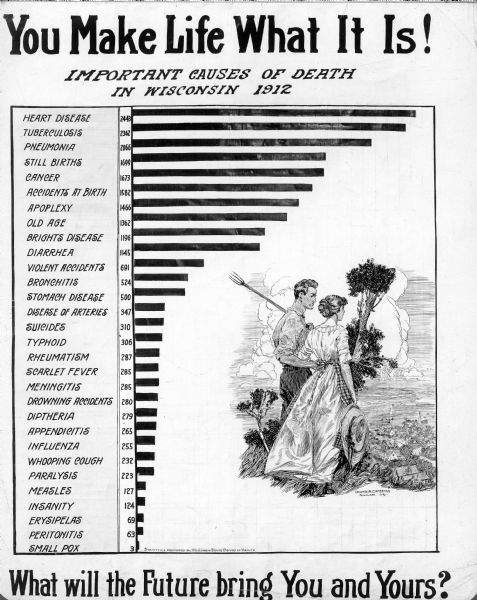

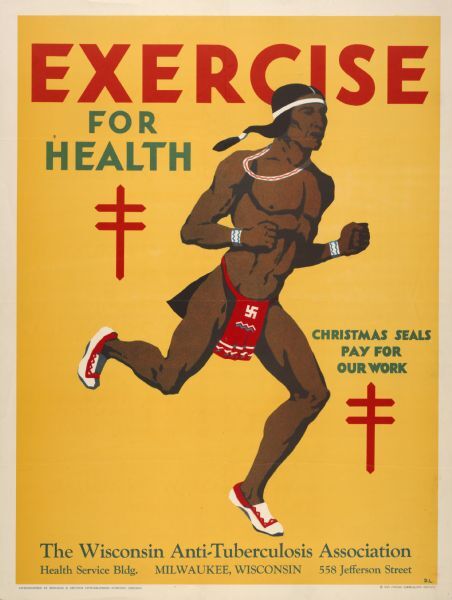

At the start of the 20th century, the way people addressed issues of health and sanitation entered a new era.

Communities took action to solve problems such as poverty, mental health, and other pressing issues. These Progressive Era reformers possessed an attitude of idealism and confidence. People believed science held the answers to age-old problems like disease, sanitation, and mental health, now an established field of medicine.

It was during this period that communities established treatment facilities like the Chippewa County Asylum. For psychologists of the time, there were two types of patients: those struggling with conditions deemed "less debilitating" or “treatable” (such as alcoholism); and the "feeble-minded," used to describe individuals with learning disabilities, cognitive impairments, and those seen as promiscuous or transgressing societal norms.

Psychologists described these patients as “a menace to public society,” without “moral instinct...[or] personal cleanliness," and "moral Perverts or Degenerates [sic] [who] take no care or thought for their own or others’ safety.”

The Progressive Era reforms built on earlier attempts to address rural poverty. Poor farms were small farming settlements where a community’s homeless, elderly, destitute, or disabled residents could live for free. In exchange, they were expected to work on the farm to the best of their ability. These were usually established at the local community level, instead of through state or federal programs.

Often, poor farm residents worked as indentured laborers, required to work under strict conditions for minimal living quarters. Many were buried in graves (sometimes unmarked) in cemeteries on the property.

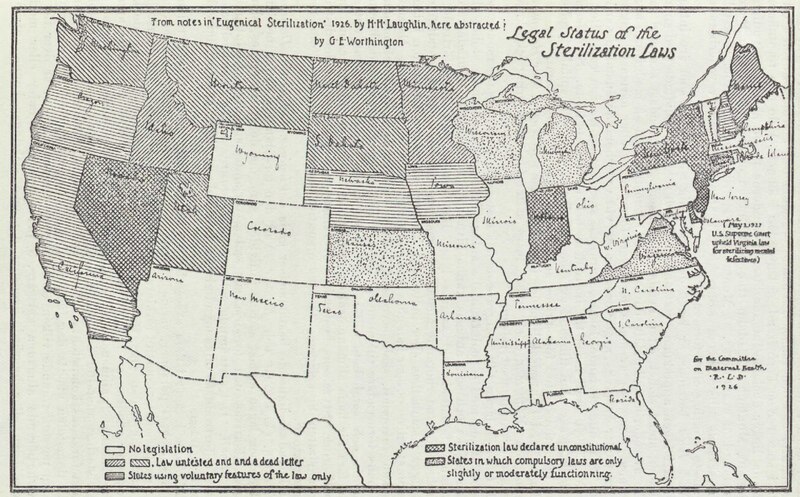

At this time, belief in eugenics—the notion that humans could breed for more desirable traits such as intelligence or self-control—grew in popularity. Most disturbingly, eugenicists argued people with characteristics deemed undesirable (criminality and behavioral or mental health issues) should have their reproduction limited or removed altogether.

While today eugenics is rightly understood as a human rights violation, during the Progressive Era many saw it as a scientific "solution." Proponents peddled fears that those deemed "feeble-minded" or "mental defectives" would overpopulate and eventually overwhelm the mentally fit. Chippewa County physician C. A. Hayes reflected these beliefs in 1918, writing, “[a]s the surgeon cuts to cure the sore that will not heal, so these half-made-ups of humanity must be eliminated from the social fabric of our country [so] that our people may be made whole and clean.” The same ideologies would soon underpin the Nazi party in Germany.

By 1913, Wisconsin passed a eugenics law that targeted "mental defectives" and epileptics for sterilization. Social mores of the era made women particularly vulnerable to the law. Government officials often deemed women "defective" if they departed from the strict gender and sexual norms of the today. Between 1913 and 1963, around 80 percent of the more than 1,800 people sterilized in Wisconsin were women.

Intelligent men must believe in the forward march of society. They must believe that the social order is changing, and changing continually for the better, and that things formerly impossible have now become possible.

-Howard Teasdale, chairman of the 1913 Vice Committee of the Wisconsin Senate

Prostitution & Vice: public health crisis or moral panic?

The same concern for traditional gender roles can be seen in a concurrent preocupation with prostitution, which was framed as both a moral and public health crisis in Wisconsin. In 1913, reformers known as the "Vice Committee" in the state legislature decried prostitution as a "white slave trade,’" where men kept women in bondage through threat of violence. But these alarm bells spoke more to anxieties about race and gender at the time. Urbanization and the growing presence of women in the public sphere fueled anxiety among the middle class.

At the same time, towns like Beloit and Milwaukee attracted hundreds of African Americans as part of the first Great Migration, where Black Southerners moved north to find employment and escape racial violence and segregation. The Vice Committee's focus for the reports—excluding Black or Indigenous women—reflects these growing anxieties, and poses prostitution as a societal concern and public health issue only if affecting white women.

While reformers claimed to be protecting women, their conclusions echoed outdated views of women remaining in the home. Observers in the Legislature considered prostitutes to be victims of predatory men, unable to contol their own actions. They believed the solution involved giving women more freedom in their youth, so they could "settle down" by the time they were old enough to be married. This paternalistic attitude was all too common under Progressive-era reformers.

In the end, the Progressive-Era-perception of societal issues as public health crises could be both helpful and harmful. There was a certain optimism that many of society’s ills could be solved with collective reform, rather than individual responsibility by itself. Reformers genuinely believed that with enough efforts and scientific understanding, society could progress to a point where issues like alcoholism, prostitution, and mental illness could easily be remedied.

Unfortunately, their solutions all too often ignored the individual behind the issue. For example, the passage of Prohibition criminalized alcohol but ignored alcoholics’ physiological addiction. Likewise, Psychologists believed that institutionalization and sterilization for the “feebleminded” was the “humane option,” while today we see it as a clear violation of human rights and personal autonomy.

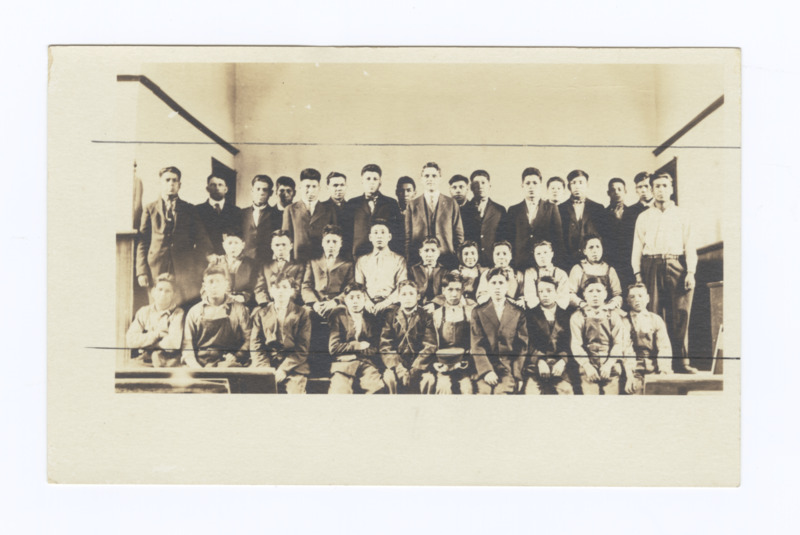

Progressive Era policies were often harmful to minority groups, as reformers rooted their policies in the idea of assimilation into broader white society, at the expense of individual people or their cultures. Native American residential schools focused explicitly on eradicating the cultural identity of Native American children and assimilating them into Anglo-American culture and religion, infamously described as “killing the Indian to save the child.” This, too, was seen as a humane solution to “the Indian Problem.” The Progressive Era’s combination of humane and idealistic motivations with unethical, flawed practice leaves the movement with a checkered legacy.