The 1918 Pandemic:

A Local & Global Crisis

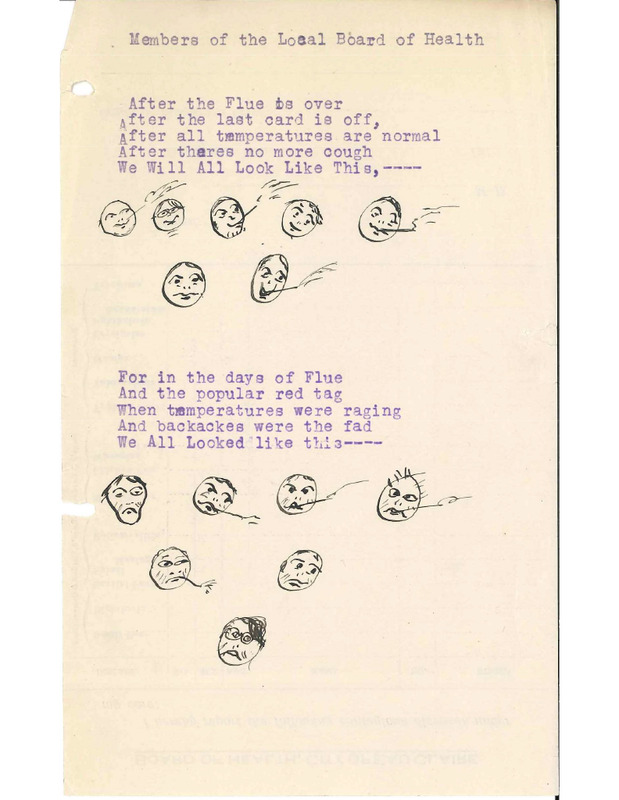

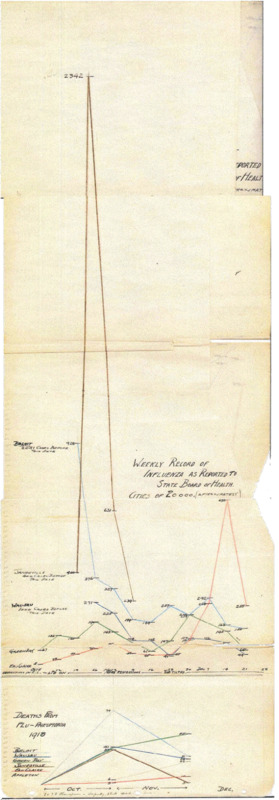

In many ways, the flu pandemic of 1918 was a precursor to COVID-19. It was the first global pandemic in an increasingly connected world, and while this led to a staggering death toll, it also led to changes in public health, as communities tried to minimize the spread. Caused by an H1N1 influenza A virus, the pandemic became the deadliest of the 20th century.

Unfortunately, governments across the globe—including the United States—largely ignored the crisis. The nation's entrance into the First World War proved to be a major distraction. Wanting to keep citizen morale high and focused on the war effort, the Wilson administration and national media across the globe downplayed the pandemic’s impact. Spain remained neutral during WWI, and were one of the few countries to communicate accurate information to the public. As a result, an influenza pandemic that likely originated in Kansas (site of the first confirmed cases in January 1918) became incorrectly known as the “Spanish Flu."

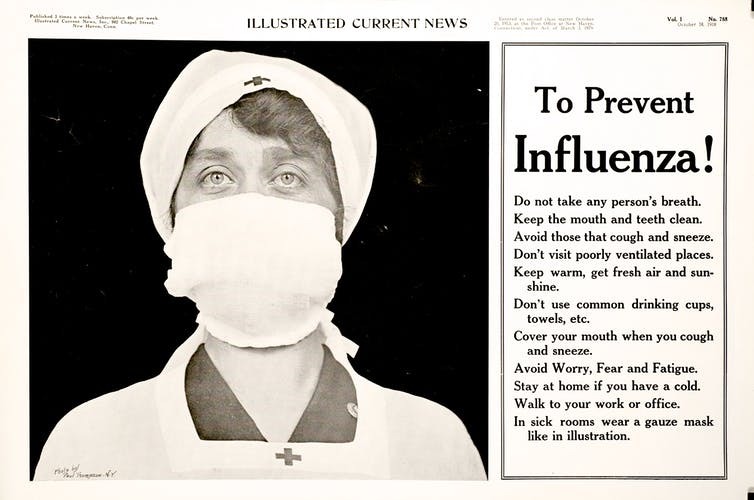

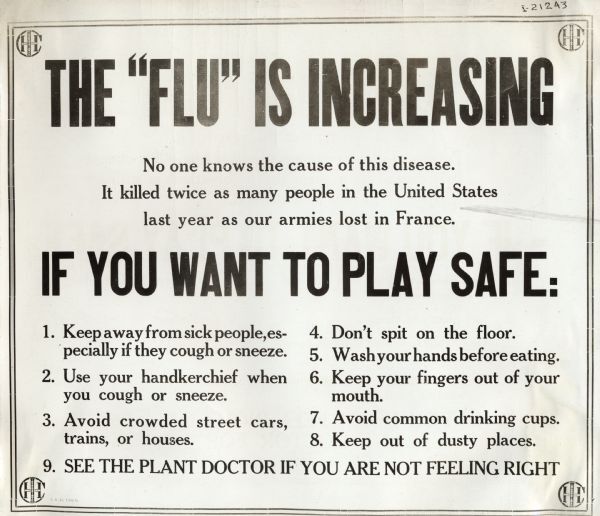

In Western Wisconsin, doctors focused on preventative care as the best way to deal with the pandemic. The Eau Claire Board of Health recommended closure of public gathering places such as ice cream parlors, saloons, restaurants, and churches. They also recommended the wearing of cloth masks and social distancing.

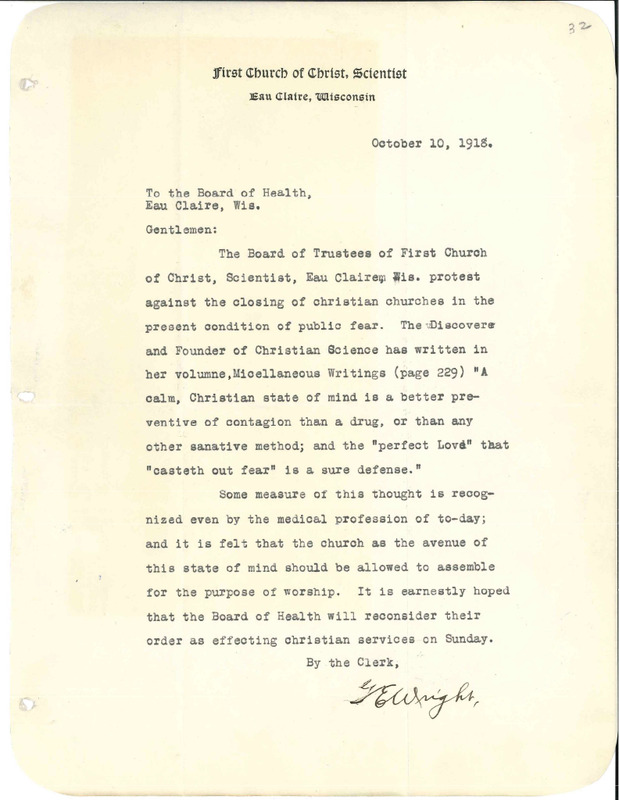

These measures were not accepted by everyone. The Church of Christian Scientists in Eau Claire protested the closure of churches. They believed that churches were important for public health because they fostered a healthy state of mind. In a time of crisis such as the ‘present condition of public fear’, they argued, churches were needed more than ever.

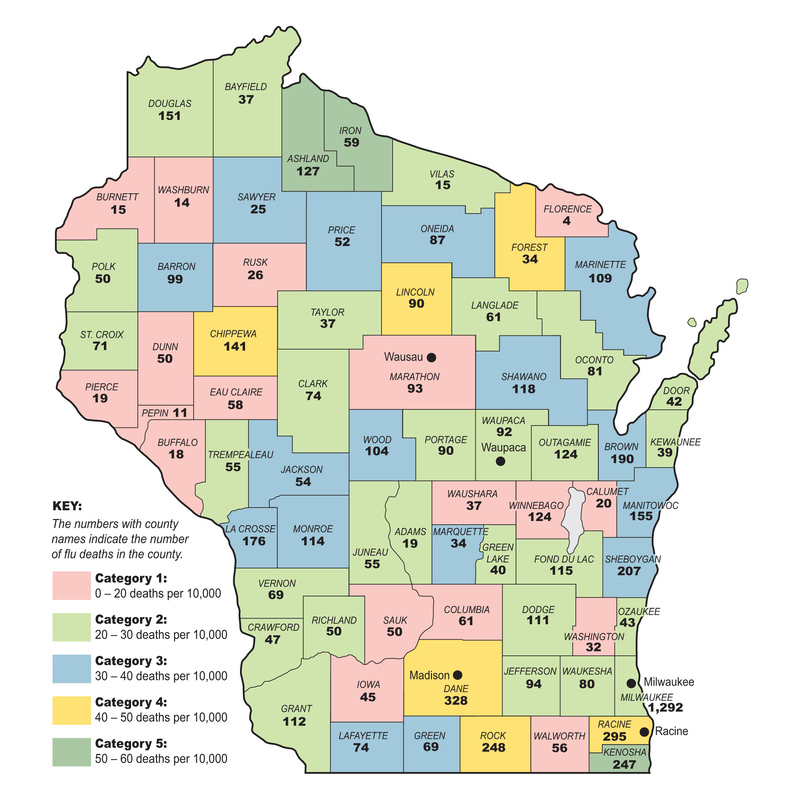

Christian Scientists rooted their arguments in the connection between public health and moral well-being, rather than the violation of religious liberties. Even when people opposed what the Board of Health was doing, they still recognized that there was a crisis and that special steps needed to be taken to end it. Overall, Eau Claire’s measures worked to keep people safe. The city had a much lower death rate than similarly-sized townships across Wisconsin.

The 1918 flu struck indiscriminately, infecting people of every community. However, the people who were hardest hit were poor communities, especially minority groups who lacked access to medical care. When a community is left to ‘fend for themselves’ without support from the rest of society, the results can be devastating, as many such communities could not afford medical care.

Although the State of Wisconsin offered some support to its municipalities, the Federal government under the Wilson administration provided virtually no help or guidance in combating the flu, which had deadly consequences. In the end, four waves of the pandemic, spanning from 1918 to 1920, had claimed the lives of roughly 675,000 in the US, and 50 million worldwide.