Confronting a Mental Health Catastrophe:

The 1980s Farm Crisis

In rural Wisconsin, the 1980s saw the peak of a different kind of far-reaching catastrophe. During the 1970s farms across the US expanded as owners purchased newer, bigger equipment, bought more land, and expanded livestock operations. As a consequence of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, a grain embargo was placed on Russia. Combined with high inflation and the austerity measures of President Ronald Reagan, farmers were not only without markets to sell their goods, but also unable to secure loans to finance their expanding operations.

Debts mounted with no relief in sight. The result was devastation for rural communities. Between 1978 and 1992, Wisconsin lost 18,546 farms, as operations big and small were overwhelmed by debt. During the toughest years of the crisis , farmers faced an economic landscape worse than the Great Depression. Facing bankruptcy or the reality of having to sell everything that represented both their livelihoods and their identities put immense stress on farmers, their families, and their communities.

Farmers had few options to deal with the profound stress, anxiety, and depression caused by the crisis. State and federal governments proved hesitant to provide meaningful assistance, and what began as an economic crisis quickly evolved into a mental health one. A 1985 study found suicide rates for farmers were twice as high as those outside their profession. Farmers over the age of 65 had a suicide rate three to four times that of the non-farming population. Rural communities did not have the infrastructure in place to address mental health issues.

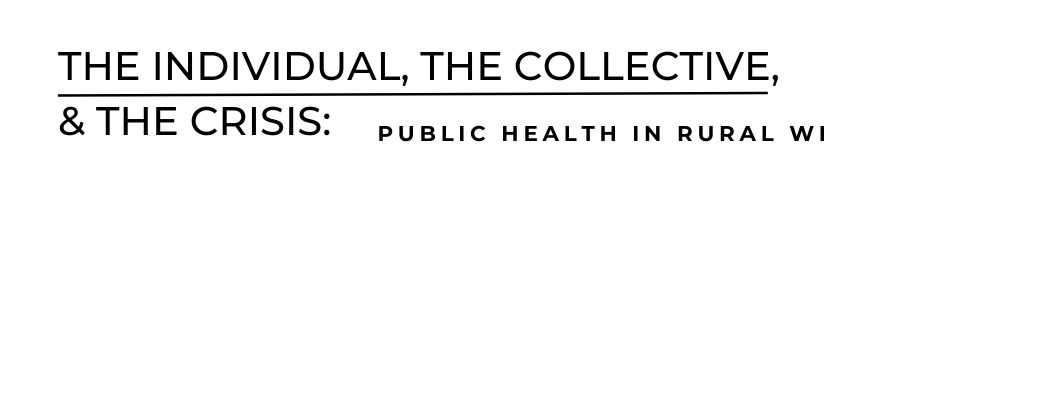

“The Mass Could not do any harm. We’ve tried everything else.”

-Stanley, WI farmer Donald Schesel

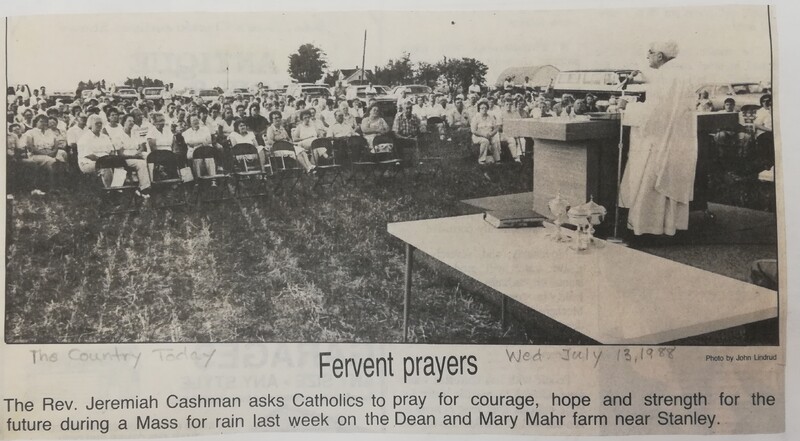

Often, local clergy would be the only community members farmers felt comfortable approaching for help, and pastors attempted to fill the void left by a lack of public health infrastructure. In the face of indifference to the crisis from state and federal officials, local communities used religion as a strong outlet for farmers desperate for help. In July 1988, 250 people attended a Catholic mass held in a burnt up alfalfa field in Stanley, Wisconsin. There, farmer Donald Schesel summed up the helplessness he and so many others felt, noting, “the Mass could not do any harm. We’ve tried everything else.”

In a 1985 letter farm activist Lee Theorin wrote, “I see family farmers losing their farm businesses, their land, their dignity, and even their families.” Lee hinted at the mental stress farmers experienced, but his focus is characteristic of activist groups of the era, working during a time when mental health concerns were largely unrecognized or dismissed in public life.

In an interview with the Lutheran Standard, farmer Douglas Harsh discussed the heartbreak and trauma of being forced to sell his 1,100-acre farm. Harsh admitted to being so depressed that he verbally abused his family. After attending a rally in Mondovi, WI—where local farmers organized to confront officials of a lending agency—Harsh discovered he was not alone in his struggles, and that losing his farm was not personal failure. Harsh was moved to become an activist, and his work brought awareness to politicians on the farm crisis, as well as establish stress hotlines providing farmers counseling for mental health issues.